Raise Against the Machine #4: Non-Fungible Families

On the limits of adaptability and interchangeability

After a long hiatus, this is a new entry in my ongoing "Raise Against the Machine" series, which focuses on parenting and family life in the technocratic age.

I've only ever read Nineteen Eighty-Four once. Perhaps that's enough. I recall C.S. Lewis' quip, when comparing the book to Animal Farm: "the shorter book seems to do all that the longer one does; and more."

That said, one scene from Nineteen Eighty-Four has been returning to my mind of late: the fate of Parsons.

Parsons is Winston's neighbour, and an ideal devotee of the Party: uncritical, timid, pliable enough to constantly bend himself and his family with great enthusiasm to the Party's ever changing whims. And yet Parsons comes a cropper. Winston finds him imprisoned in the Ministry of Truth in the final part of the novel—his own daughter, only seven years old, having dobbed him in after hearing him say "Down with Big Brother!" in his sleep.

Parsons is Orwell's illustration of one of the most basic elements of totalitarianism: undermining the family. The Party can only thrive and dominate in Orwell's dystopia because it creates a world in which children are inwardly prised away from their parents. Ironically, Parsons himself is the one who raised his daughter this way. "I don't bear her any grudge for it," he says of the betrayal. "In fact I'm proud of her. It shows I brought her up in the right spirit, anyway."

It clearly never crosses Parsons' daughter's mind that it will adversely affect her to lose her own father. And the true terror of Orwell's novel, of course, is that she may well love Big Brother so sincerely that it pains her not at all.

For the Party, all children must be fungible. "Fungible" has two meanings: either entirely interchangeable or entirely adaptable. It is the latter I have in mind here.

Nineteen Eighty-Four's children must be so utterly transferrable and flexible that it doesn't actually matter which adults they are with. It could be mother, father, teacher, nursery nurse, Party delegate, whoever. All are merely the avatars of Big Brother. He is the one who matters in the end. His is the firmest and most loving hand. If the Party can convince children (and parents) of this, then the hard work is already done. Why would it matter if your father were taken away when you still have Big Brother?

Insightful dystopian writers like Orwell are usually interested not in the future but the present. Often the only difference between their imagined worlds and our own is that the undesirable conditions in the fiction came about with just a sliver more intentionality and evil moustache-twirling than did the essentially identical conditions in ours.

Parents today are expected to raise fungible children. Our children must be easy to hand over to other caregivers, first at nursery and then in school. The former is supposedly good preparation for the latter, which in its turn is meant to be good preparation for university and finally "working life."

If either parents or children struggle with this arrangement for anything more than the first day or two, it is generally regarded by everyone else as a parental failure. The expectation is that children should easily adapt to being away from their parents, and indeed that it is a parental duty to prepare them thoroughly for this.

What's more, it is assumed that parents are desperate for this to happen and that, after a few "first day of school" sniffles, it will be of no odds to them that they have, supposedly of their own volition, been separated from their children. If they have reservations about this, they are given the side-eye. Many keep their doubts to themselves, and even then they self-rebuke. I think again of Parsons:

'Are you guilty?' said Winston.

'Of course I'm guilty!' cried Parsons with a servile glance at the telescreen. 'You don't think the Party would arrest an innocent man do you?' His froglike face grew calmer, and even took on a slightly sanctimonious expression. 'Thoughtcrime is a dreadful thing, old man,' he said sententiously.

The same thinking, sadly, is often at work in the church. The assumption runs rife that parents should be enthusiastic about removing their children from the church service (having been already largely separated from them during the week), and that they should be entirely comfortable with forcing a distressed child through creche or Sunday school. Later, the assumption often arises on both sides that parents do not need to take on discipling their children because it can be done by their youth leaders. If you have reservations about this system, your commitment to both your own and your children's spiritual health comes under suspicion.

As well as assuming that children should be fungible in the sense of being adaptable, this whole system assumes also that adults are fungible in the other sense: of being essentially interchangeable. The unique and indispensable role of parents (and within that the specific roles of mothers and fathers) is eclipsed. This adult fungibility, however, only goes so far. Many of the professional "caregivers" in the system in fact regard themselves as better suited to the task than parents and seek actively to drive a wedge between parents and children. Parents are a hindrance to the teacher's mission to increase the child's fungibility.

This desire for fungible children is often sold as merely "socialisation" or as "preparing them for the next stage". Certainly, children need to mix with others and parents need to prepare them to stand on their own two feet. But this is simply not the same as what we do with our children today, especially the very youngest. In fact, we often do the opposite. School and nursery often hinder socialisation, in part because they deprive children of the unique and richly textured relationships of family life, in favour of an arbitrary group of local children (with who knows what dysfunctions) who happened to be born in the same twelve month September-August period. Further, school and nursery often do not serve as a good preparation for future life, for reasons that are almost too numerous to mention.

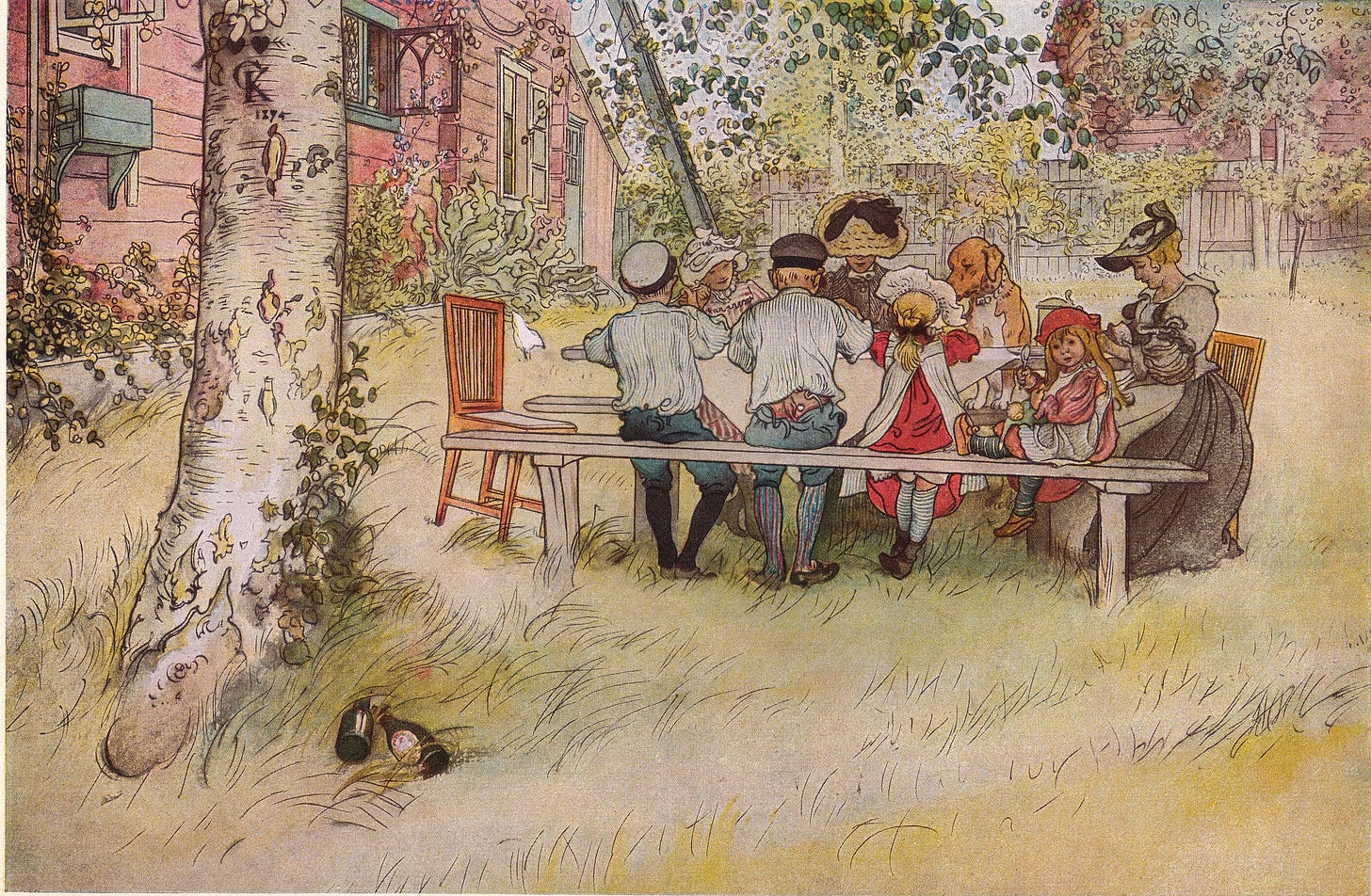

An essential part of learning to raise against the Machine is to realise that children and their parents are not fungible in either sense of the word. The unique, God-given contours of each mother's affection, of each father's discipline, of each sibling's play, are as irreplicable as fingerprints. Certainly it takes a village to raise a child. But this is not the same thing as training our children to be endlessly adaptable to an ever-changing carousel of interchangeable adults and peers.

Although it is not as explicit as Parsons' loyalty to the party, our willingness to follow the script we are given in this area is the same phenomenon: a perverse willingness to have wedges driven between the members of our household in the name of something which we imagine precedes or supersedes the family. And when those gaps open up, the Machine fills them very, very swiftly.